The Mythical Man-Month - Overview

Review

The Mythical Man-Month is a book 1975 by Fred Brooks, in which he discusses his insights into the difficulties of managing a software engineering projects based on his experience working on the IBM OS/360 during the 1960’s. The book has endured the passage of time, not because of the great technical or technological details that it dives into, but rather because of the lack of them. While one might be quick to assume that a book about managing teams of software engineers would delve into the niches and gritty details of such an emerging field, especially considering the date it was published, the book’s focus is rather on the human and managerial aspect of these projects. As such, while being a technological book, a lot of the ideas discussed can be extrapolated to any kind of large human endeavor, and as such its reading can still provide insights for the modern software developer. The prime example of this characteristic is the maxim of the book, Brook’s Law, which states: ‘adding manpower to a late software project makes it later’.

Let’s explore this statement a little further. At first, such a notion might seem counterintuitive, if you are running late on something, why would adding more people would be detrimental? Wouldn’t it better distribute the overall workload between more hands? In theory yes, and in simple tasks that can be easily divided that is indeed the case. However, software projects are inherently complex, in such a way that a new member of any given team can’t be assigned and expected to perform at the same level some other member who’s been there since the start, as this new member needs to understand all of the little details, entangled interconnections, logic flows, etc. This adjustment period, or even training one, will inevitably set back the team even further, as extra time and effort is devoted to getting the new members up to speed. So, we arrive at the pivotal idea of this book: men and months are not interchangeable.

The book, however, doesn’t just leave us with a bleak outlook for the future of software projects, yet it also doesn’t delude us into a false sense of security promising fictitious solutions of perfect efficiency. Rather, the book focuses on analyzing the common pitfalls that plagued the software environment back in those days, such as bas estimations of time, poor organizational structure, overreaching and overloading with features, pride and selfishness in the organization, poor communication, disregarding non-technical work, failing to account for the size and time limitations, ignoring warning sings, and such on. The bug then argues that even though we will probably never stumble upon some magic technique that solves all of the inefficiencies of software development, being mindful of all of these ills and striving to contain them will, in addition, help software development escape from the awkward place is it currently placed.

Conclusions

While an interesting and insightful read, I must admit that the age of the book itself was a bit of a hurdle for me. The technology the author talks about will definitely trip you up if you don’t have some sort of background knowledge of the projects and developments mentioned, but it isn’t a deal breaker, as some google searches aid immensely in getting the background necessary to get a better picture of the world this book was conceived in. As mentioned above, the main appeal of the book still stands, which is that of the many difficulties one might encounter while developing a software product, and some of the ideas to better tackle these challenges and avoid common pitfalls. While some of the technological concerns have definitely shown their date due to the incredible development of machine power over the last 50 years (such as micro-managing even the smallest pieces of memory), most of the ideas still hold their value since the book focuses on the human aspect much more than the technological one.

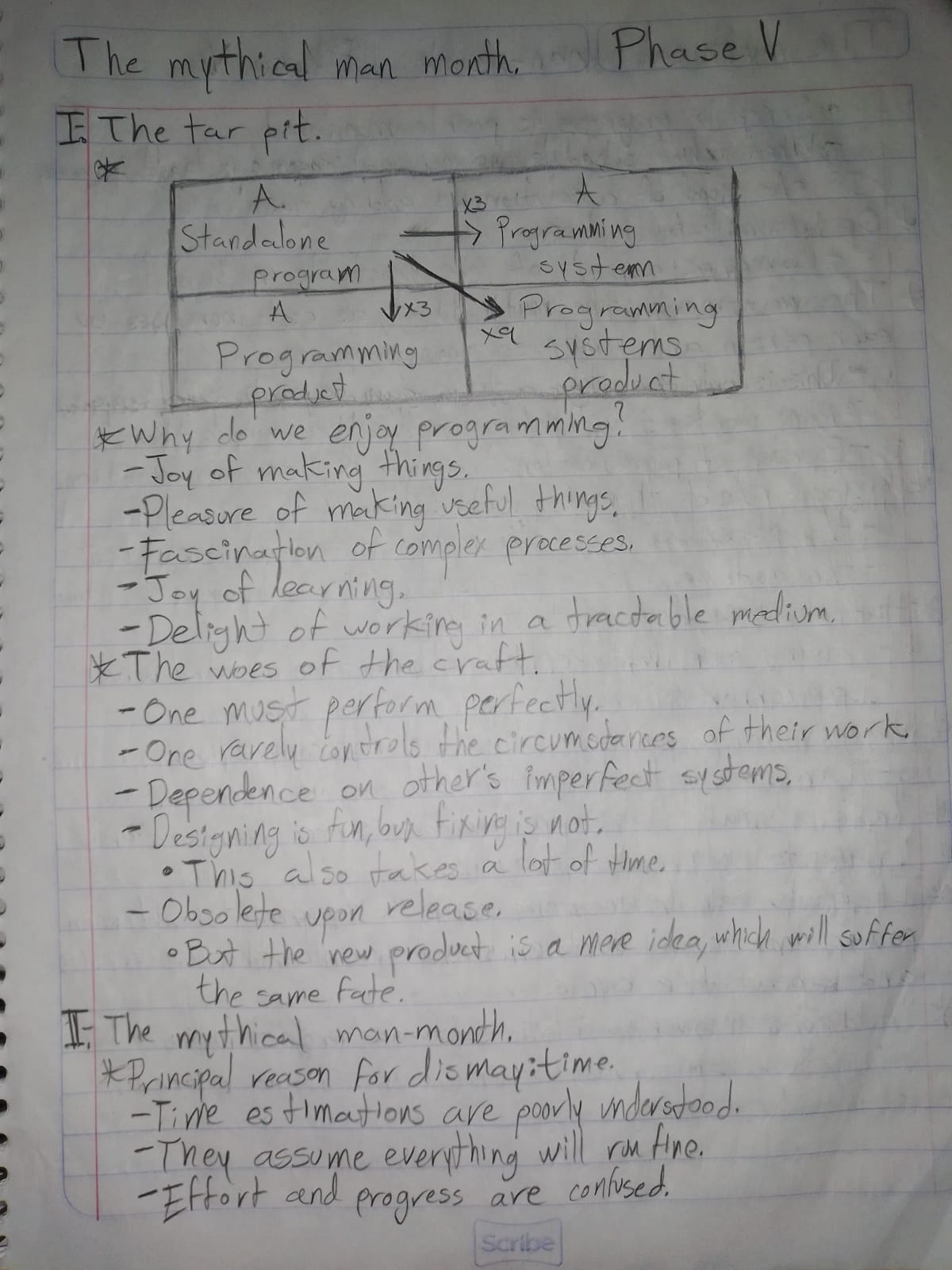

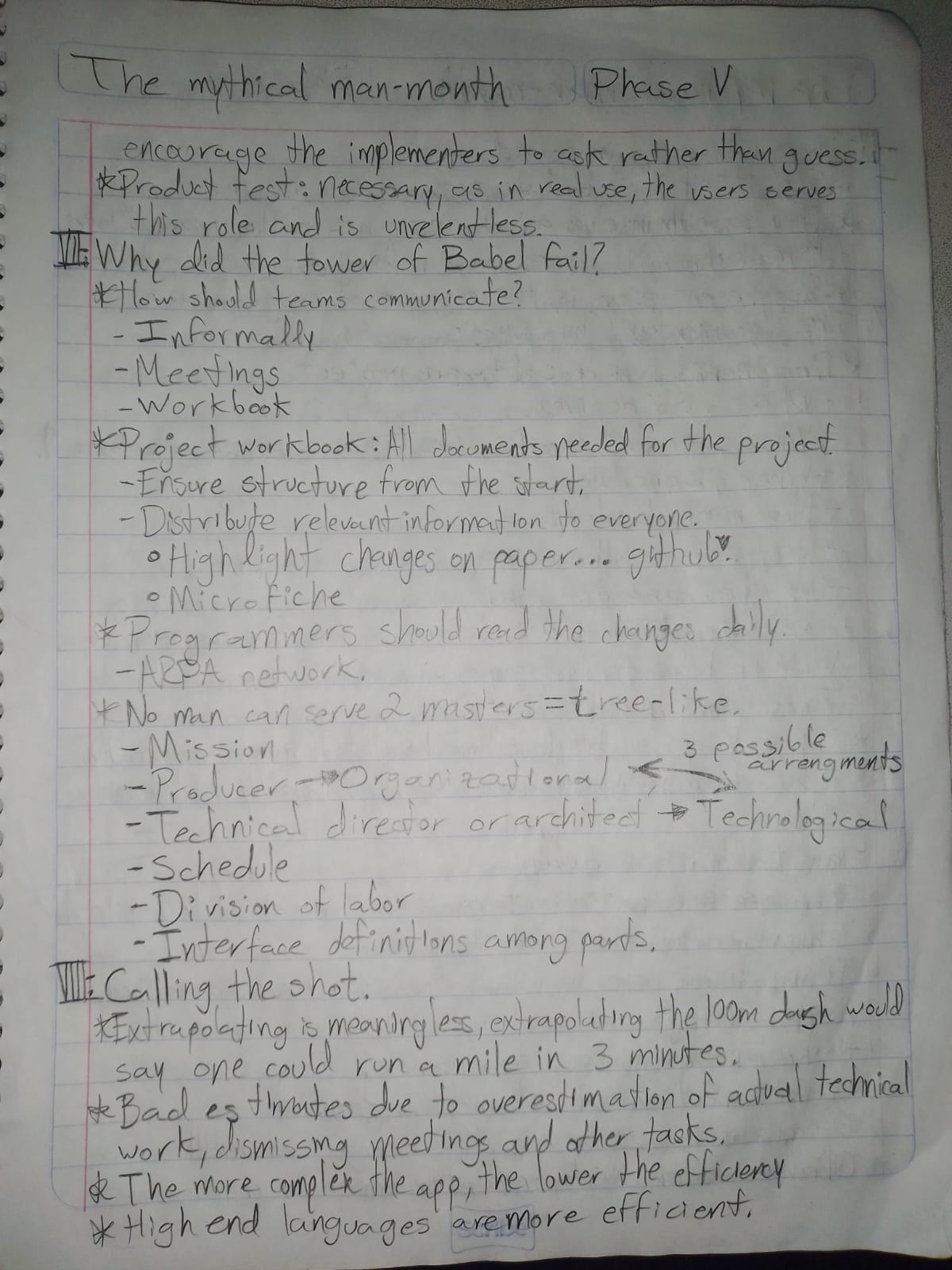

Sketches

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)